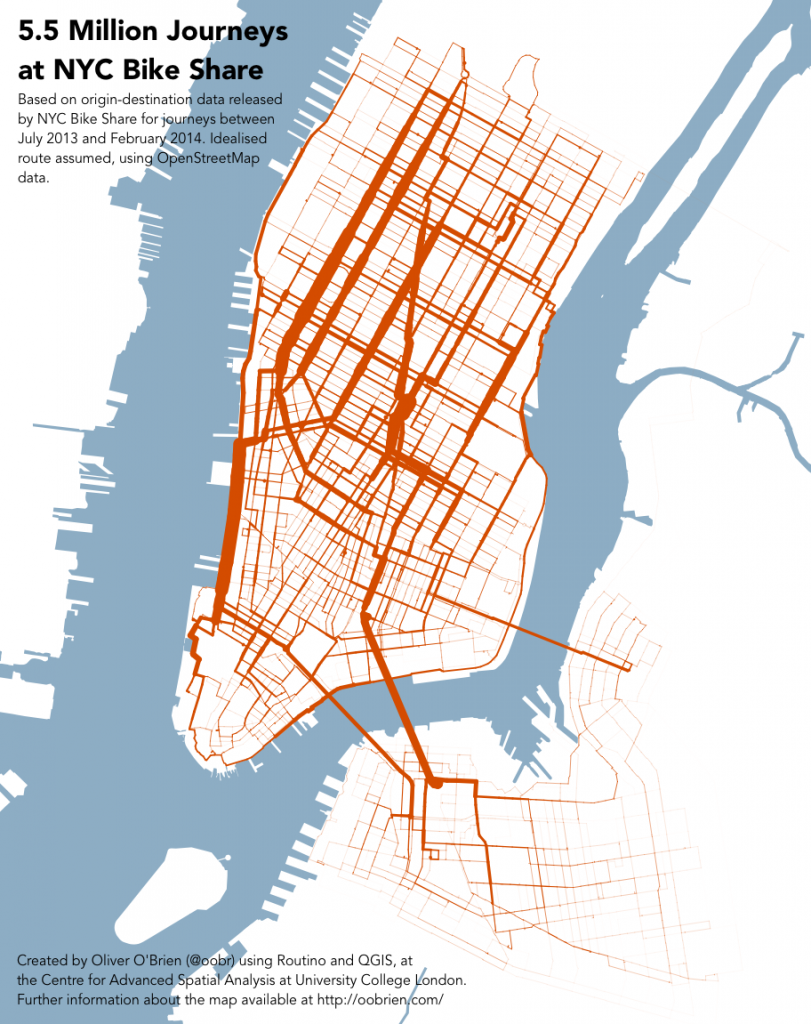

5.5 Million Journeys at NYC Bike Share

[Updated – timeperiod-split maps added] Following on from my London bikeshare journeys graphic, here is the same technique applied with the data released by NYC Bike Share (aka Citi Bike) earlier this week.

If you look carefully at the full size map you can see a thin line heading north-eastwards, initially well out of the bikeshare “zone”, representing journeys between Williamsburg and Central Park, via the Queensboro Bridge cycle path. We see a similar phenomenon for journeys between Tower Bridge and Island Gardens in London. Whether any of the riders actually take this route, of course, is open to question – they might take a longer – but more familiar – route, that stays more within the area of the bikeshare.

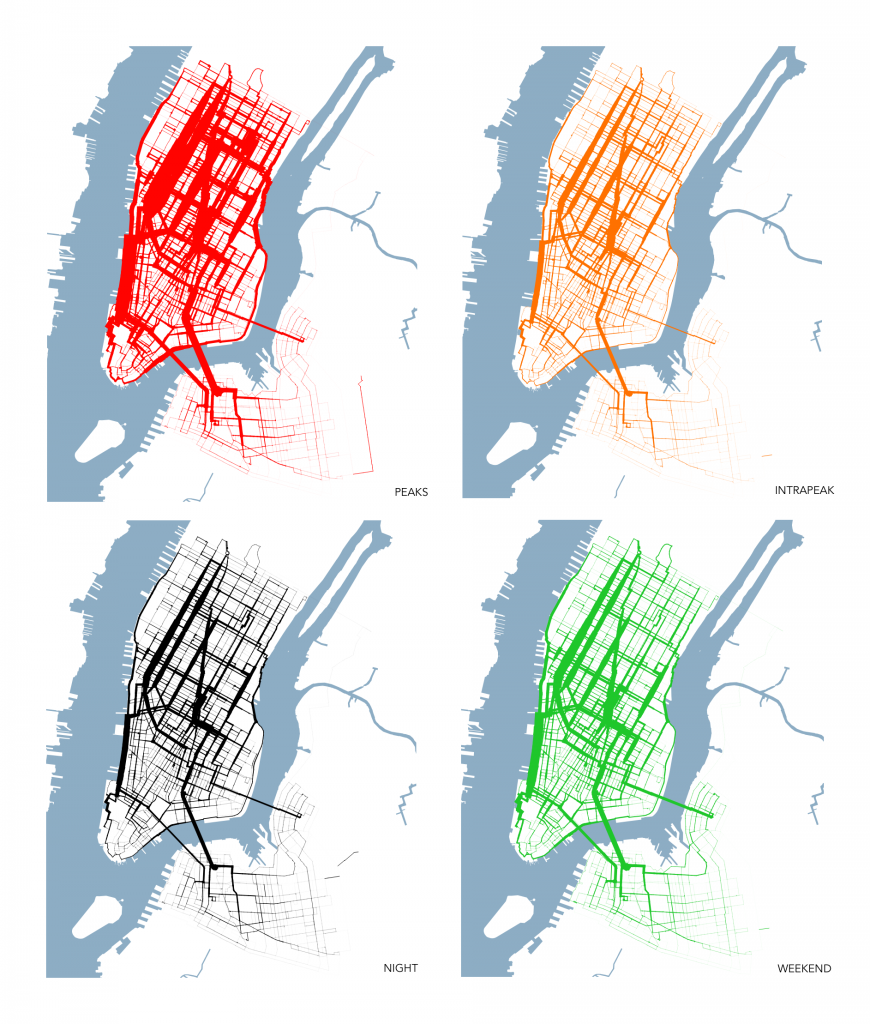

Below is a version of the graphic with the data split into four timeperiods – weekday rush-hour peaks (7-10am and 4-7pm starts), weekday interpeak (10am-4pm), weekday nights (7pm-7am) and finally weekends. The data is scaled so that the same thicknesses of lines across the four maps represent the same number of journeys along each street segment – but bear in mind that there are fewer weekends than weekdays. While, as would be expected, the rush-hour peaks see the most number of journeys, there is less spatial variation across the city, between the four timeperiods, than I expected. Click on the graphic for a larger version.

The graphics were produced by creating idealised routes (near-shortest path, but weighted towards dedicated cycle routes and quieter roads) between every pair of the ~330 docking stations in the system, using Routino and OpenStreetMap data (extracted using the Overpass API). Edge weights were then built up using a Python script, a WKT file was created and then mapped in QGIS, with data-based stroke widths applied from the weights.

The routes are only as good as the OpenStreetMap data – I think the underlying data is pretty good for NYC, thanks to great community work on the ground, but there is still a possibility that it has missed obvious routes, or proposed wacky ones. It also doesn’t account for journeys starting or ending at the same place, or journeys where the prime purpose is an exploration by bike – with the user unlikely therefore to take an “obvious” A-B route.

Even with that caveat, it’s still a revealing glimpse into the major route “vectors” of bikeshare in New York City.