The Cold War years are usually presented in terms of the military force and an ever expanding resource of military equipment. This of course includes foremost the nuclear weapons both sides the West lead by the U.S. and the NATO and the Communist East lead by Russia.

Architecture however, played an important role in cicvil defence and the preparation for a potential third world war. There was far less attention payed to the fact that all nations had programs running to prepare their societies for the case of escalation. Tensions there were enough.

Nuclear war was the ultimate danger and with images and evidence form Hiroshima and Nagasaki preparation was part of civil defence programs also in the U.S. In a new book Fallout Shelter: Designing for Civil Defence in the Cold War published by University of Minnesota Press, David Monteyne presents these U.S. programs from an architectural perspective. This detailed investigation ranges from the propaganda to built examples and examines closely the role of the architect as the middle man between government and civil society implementing a plan that is further reaching than simply the provision of shelter. Find Fallout Shelter: Designing for Civil Defence in the Cold War for great prices with these Amazon Promo Codes.

Image taken from etsy / DIY fallout shelter for your back garden.

As Monteyne points out in his introduction it effectively is a contract between citizens and government exchanging provision for shelter and quality of live for cooperative behaviour. He refers to Foucaults biopower as a political relationship. Essentially building shelters was and in some cases still is, as we’ll discuss further on, the physical implementation of goals and powers of the welfare state.

The book explores in seven chapters the background, the planning, the implementation and the potential influence of shelter provision programs in the U.S. The programs were mostly about information and education but of course also aiming to build shelter provision. For this the architects were a key alley and the American Institute of Architects (AIA) launched a series of design competitions together with the Office for Civil Defense (OCD). The aim was to promote good planning and preparation for shelter provision. A series of designs were presented as winners, both built and as projects.

In the last chapter Monteyner goes a step further and applies his observations and investigations as an interpretation of an architectural style. He goes as far as arguing that this focus on shelter and bunker design has effectively led to an specific style, not a new one, but Brutalism?! Well thats something new and of course he has some evidence, the famous Boston City Hall. The basic argument is that Brutalist architecture looks a bit like bunk architecture so the origin of Brutalism is to be found in these government programs during the early Cold War times having shaped a whole generations concusses.

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Brutalism

Image taken from Wikipedia / The Boston City Hall that serves as an example as to how bunker design has lead to the Brutalism movement.

Boston City Hall is at this point is the famous and widely debated example in the U.S. and serves well since it has implemented to some extend the requirements for fallout shelter. Interestingly the term Burtalism however is claimed to be coined by the Smithsons from the United Kingdom based on Le Corbusier in the context of CIAM. So not really an American connection there and all in all a bit too early for these programs that were run in the fifties and sixties mainly.

Reading the shelter guides these cold war programs produced and the resulting designs one can not help but smile. It amazing how naive the designs are and how improvised. For example there are guides on how to build a wooden shelter in your backyard and even the Boston City Hall project, the famous bunker style building has implemented shelter space on the eights floor?

It seemed to work and to some degree the American officials seemed to gain some sense of preparednes from these exercises. To everyone else these plans must immediately seem strange. If all you need to withstand a nuclear war is to build the entrance of a house not in line with the corridor to prevent fallout from penetrating deep into the house we ar all save.

American architecture is not generally well known for going deep underground and if possible basements are avoided at any cost. Very much so in terms of shelter and fall protection provision. Not even these programs have seriously considered building bunker underground, as the Boston City Hall projects demonstrates. Shelter can happily be provided on the eighth floor?!

The way this infrastructure of bunkers and shelters is described in the publication does echo practices for example in Switzerland. The small country in the heart of Europe is well known for its specific bunker infrastructure. On the military end this infrastructure was designed to guarantee the independence creating a réduit in the alps. On the civil side planning for large scale shelter infrastructure started a early as the 1930s. These efforts were geared towards the provision of shelter everyone in the country. Doring the 1980s this was achieved, making Switzerland arguably the leading provider of shelters.

It is a general requirement in Switzerland to built a shelter as part of every housing project ranging from a single family house to an entire block. Depending on the size of the project and number of inhabitants the shelter has to provide a certain capacity. Currently there are, according to the Swiss Federal Office for Civil Protection FOCP, about 360’000 individual shelters built as part of buildings and in addition some 2300 communal shelters. Hereby a shelter in general is a sort of mini bunker in the basement of every building constructed after 1963.

Image taken from Kanton Schwyz / Detailed section drawing showing the emergency exit from a standard single family house shelter space. Requirements including distances and dimensioning are based on standards applicable through out Switzerland. Note also the shown solution in case of high ground water.

There are clear guide lines for the construction of the shelter, the provisions and the equipment necessary. Every opening has to have a massive concrete door to completely seal the space. There is ventilation equipment required, designed to withstand gas and fall out. In addition there are simple bunk bed constructions and basic facilities such as dry toilets required.

Larger buildings such as community centres provide shelter for a larger number of people ranging from 30 to a few hundred. All are real bunkers constructed in full concrete, at least 25 cm in thickness with completely sealable openings, basic infrastructure equipment, toilets, beds and cooking facilities.

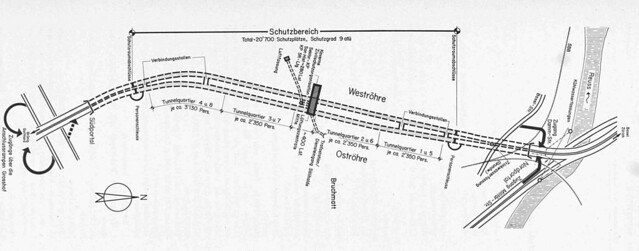

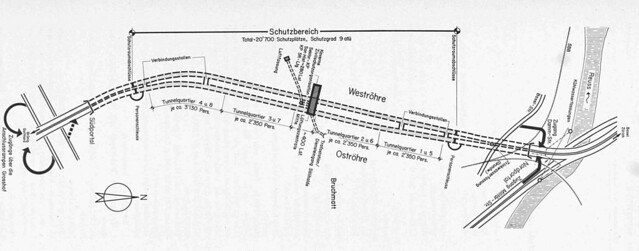

In addition infrastructure projects sometimes have been used to extend capacity of shelter place capacity. For examples the highway tunnel ‘Sonnenbergtunnel‘ in Luzern was build with the capacity to transform into a massive bunker if required. It would have provided places for about 20’000 people. This includes sanitary facilities including a small hospital unit, large kitchens, ventilation infrastructure and bunk beds and so on. In case of emergency each tunnel entrance would be closed with a specially designed massive concrete gates to seal the entrance. The entire length of the tunnel be used for cubicles with bunk beds. It was calculated for 1m2 of floorspace per person.

Image taken from Luzernerzeitung / The large gates of the Sonnenbergtunnel shelter in Switzerland were last closed in 1987. The gate is constructed on sight and is curved to withstand great pressure.

Sonnenberg tunnel is since 2005 no longer in operation as a shelter unit. It can still be visited with a guided tour though. The city of Luzern has in connection to the complete renovation of the highway A2 developed a new Civil Defence concept and provides the capacity in shelter places elsewhere. However, through out switzerland a number of other such invisible underground civi defence infrastructure buildings are still being maintained in order to provide shelter in case of war or nuclear fall out.

Switzerland has in many ways optimised and multiplied the implementation of shelter provision for the civil population. Reading it under the aspects David Monteyne presents in the introduction to his publication the outreach of the state to discipline the population to good behaviour in exchange for welfare did work and still works very well. It can be argued that the Swiss population and the architects as the implementers of these outreach programs cooperate well. However, the implementation of the shelter infrastructure is taken much more serious in its mechanics in Switzerland than according to Monteyne it was in the US. And from a Swiss perspective to speak of a specific bunker style (believed to be brutalism) to emerge from the state requirements for shelter seems absurd. This is mainly dueto the fact that Swiss planners have always decided that shelter or bunker facilities only really make sense if they are implemented in the basement and never tried to somehow fit it in above ground. As such the shelter has never been visible and therefore did not influence the ascetics of the aboveground appearance necessarily.

Details taken from: Heierli, W., Jundt, L. & Kessler, E., 1976. Die Zivilschutzanlage Sonnenbergtunnel in Luzern. Schweizerische Bauzeitung, 94(46), pp.689-699.

/ Map of the Sonnenberg highway tunnel near Luzern in Switzerland showing the location of the built shelter. The bunke was designed to provided space for 20’000 civilians in the case of war. Constructed between 1971 and 1976. The shelter was finally closed in 2005.

Details taken from: Heierli, W., Jundt, L. & Kessler, E., 1976. Die Zivilschutzanlage Sonnenbergtunnel in Luzern. Schweizerische Bauzeitung, 94(46), pp.689-699.

Building shelters underground could be an explanation why the required provision of shelter had and still has a much higher acceptance through out the civil population. Without it being constantly present in the everyday environment it is much more a background infrastructure than an style and other functions are not overloaded by the required provision of shelter but extended.

Nevertheless the book presents a very distinct characteristic of the last century and the period between 1950 and 1980. Whether it lead to a distinct architectural style can be debated. What is of specific interest is to compare the different approaches to the provision of shelter as well as what these approaches tell about how the civil society deals with chaos and order, the manipulation of the collective and the individual and the role of planning and architecture in a wider society context.

Image taken from amazon / Book cover.

Monteyne, D., 2011. Fallout Shelter: Designing for Civil Defense in the Cold War, University of Minnesota Press.

Continue reading »