Special Sessions on GeoComputation @ NARSC

–>

The latest outputs from researchers, alumni and friends at the UCL Centre for Advanced Spatial Analysis (CASA).

–>

–>

Over the last few months we have been working on developing a agent-based model which explores the spread and containment of tuberculosis. Today is the first time that we show the model to a academic audience at the AAG Annual meeting. To give a sense …

Continue reading »

Over the last few months we have been working on developing a agent-based model which explores the spread and containment of tuberculosis. Today is the first time that we show the model to a academic audience at the AAG Annual meeting. To give a sense …

Continue reading »

Over the last few months we have been working on developing a agent-based model which explores the spread and containment of tuberculosis. Today is the first time that we show the model to a academic audience at the AAG Annual meeting. To give a sense …

Continue reading »

Recently the USGIF published a book entitled “Human Geography: Socio-Cultural Dynamics and Global Security” in which we have a chapter called “Social Media and the Emergence of Open-Source Geospatial Intelligence”. This book has been some time in…

Continue reading »

Recently the USGIF published a book entitled “Human Geography: Socio-Cultural Dynamics and Global Security” in which we have a chapter called “Social Media and the Emergence of Open-Source Geospatial Intelligence”. This book has been some time in…

Continue reading »

Recently the USGIF published a book entitled “Human Geography: Socio-Cultural Dynamics and Global Security” in which we have a chapter called “Social Media and the Emergence of Open-Source Geospatial Intelligence”. This book has been some time in…

Continue reading »

“(i) to contribute to the dissemination of the recent research and development of the use of information and communication technologies (ICT) in urban and spatial planning, trying to demonstrate their usability in planning processes through the presentation of relevant case studies, framed by their underlying theory; (ii) to give additional evidence to the fact that ICT are the privileged means to produce virtual cities and territories; and (iii) to make available, from a pedagogical standpoint, a group of illustrative reviews of the scientific production made by both academics and practitioners in the field.”

The book has 11 chapters which are grouped in several themes:

“first group focuses on the discussion over the use of ICT in spatial planning; the second group of contributions deals with urban modelling and simulation; the third group focuses on the use of different sensors to acquire information and model spatial processes; the fourth group focuses on the use of data to create more capable visualization tools; and the fifth group is about the use of virtual models to simulate real environments and plan and manage other aspects of the built environment such as energy.”

Cities provide homes for over half of the world’s population, and this proportion is expected to increase throughout the next century. The growth of cities raises many questions and challenges for urban planning including which cities and regions are most likely to grow, what the pattern of urban growth will be, and how the existing infrastructure will cope with such growth. One way to explore these types of questions is through the use of multi-agent systems (MAS) that are capable of modeling how individuals interact and how structures emerge through such interactions, in terms of both the social and physical environment of cities. Within this chapter, the authors focus on how MAS can lead to insights into urban problems and aid urban planning from the bottom up. They review MAS models that explore the growth of cities and regions, models that explore land-use patterns resulting from such growth along with the rise of slums. Furthermore, the authors demonstrate how MAS models can be used to model transportation and the changing demographics of cities. Through these examples the authors also demonstrate how this style of modeling can give insights into such issues that cannot be gleamed from other modeling methodologies. The chapter concludes with challenges and future research directions of MAS models with respect to capturing the dynamics of human behavior in urban planning.

Full Reference:

Continue reading »Crooks, A.T., Patel, A. and Wise, S. (2014), Multi-agent Systems for Urban Planning, in Pinto, N.N., Tenedório, J. Antunes A. P. and Roca, J. (eds.), Technologies for Urban and Spatial Planning: Virtual Cities and Territories, IGI Global, Hershey, PA, pp. 29-56. (pdf)

“(i) to contribute to the dissemination of the recent research and development of the use of information and communication technologies (ICT) in urban and spatial planning, trying to demonstrate their usability in planning processes through the presentation of relevant case studies, framed by their underlying theory; (ii) to give additional evidence to the fact that ICT are the privileged means to produce virtual cities and territories; and (iii) to make available, from a pedagogical standpoint, a group of illustrative reviews of the scientific production made by both academics and practitioners in the field.”

The book has 11 chapters which are grouped in several themes:

“first group focuses on the discussion over the use of ICT in spatial planning; the second group of contributions deals with urban modelling and simulation; the third group focuses on the use of different sensors to acquire information and model spatial processes; the fourth group focuses on the use of data to create more capable visualization tools; and the fifth group is about the use of virtual models to simulate real environments and plan and manage other aspects of the built environment such as energy.”

Cities provide homes for over half of the world’s population, and this proportion is expected to increase throughout the next century. The growth of cities raises many questions and challenges for urban planning including which cities and regions are most likely to grow, what the pattern of urban growth will be, and how the existing infrastructure will cope with such growth. One way to explore these types of questions is through the use of multi-agent systems (MAS) that are capable of modeling how individuals interact and how structures emerge through such interactions, in terms of both the social and physical environment of cities. Within this chapter, the authors focus on how MAS can lead to insights into urban problems and aid urban planning from the bottom up. They review MAS models that explore the growth of cities and regions, models that explore land-use patterns resulting from such growth along with the rise of slums. Furthermore, the authors demonstrate how MAS models can be used to model transportation and the changing demographics of cities. Through these examples the authors also demonstrate how this style of modeling can give insights into such issues that cannot be gleamed from other modeling methodologies. The chapter concludes with challenges and future research directions of MAS models with respect to capturing the dynamics of human behavior in urban planning.

Full Reference:

Continue reading »Crooks, A.T., Patel, A. and Wise, S. (2014), Multi-agent Systems for Urban Planning, in Pinto, N.N., Tenedório, J. Antunes A. P. and Roca, J. (eds.), Technologies for Urban and Spatial Planning: Virtual Cities and Territories, IGI Global, Hershey, PA, pp. 29-56. (pdf)

“(i) to contribute to the dissemination of the recent research and development of the use of information and communication technologies (ICT) in urban and spatial planning, trying to demonstrate their usability in planning processes through the presentation of relevant case studies, framed by their underlying theory; (ii) to give additional evidence to the fact that ICT are the privileged means to produce virtual cities and territories; and (iii) to make available, from a pedagogical standpoint, a group of illustrative reviews of the scientific production made by both academics and practitioners in the field.”

The book has 11 chapters which are grouped in several themes:

“first group focuses on the discussion over the use of ICT in spatial planning; the second group of contributions deals with urban modelling and simulation; the third group focuses on the use of different sensors to acquire information and model spatial processes; the fourth group focuses on the use of data to create more capable visualization tools; and the fifth group is about the use of virtual models to simulate real environments and plan and manage other aspects of the built environment such as energy.”

Cities provide homes for over half of the world’s population, and this proportion is expected to increase throughout the next century. The growth of cities raises many questions and challenges for urban planning including which cities and regions are most likely to grow, what the pattern of urban growth will be, and how the existing infrastructure will cope with such growth. One way to explore these types of questions is through the use of multi-agent systems (MAS) that are capable of modeling how individuals interact and how structures emerge through such interactions, in terms of both the social and physical environment of cities. Within this chapter, the authors focus on how MAS can lead to insights into urban problems and aid urban planning from the bottom up. They review MAS models that explore the growth of cities and regions, models that explore land-use patterns resulting from such growth along with the rise of slums. Furthermore, the authors demonstrate how MAS models can be used to model transportation and the changing demographics of cities. Through these examples the authors also demonstrate how this style of modeling can give insights into such issues that cannot be gleamed from other modeling methodologies. The chapter concludes with challenges and future research directions of MAS models with respect to capturing the dynamics of human behavior in urban planning.

Full Reference:

Continue reading »Crooks, A.T., Patel, A. and Wise, S. (2014), Multi-agent Systems for Urban Planning, in Pinto, N.N., Tenedório, J. Antunes A. P. and Roca, J. (eds.), Technologies for Urban and Spatial Planning: Virtual Cities and Territories, IGI Global, Hershey, PA, pp. 29-56. (pdf)

Some ideas take long time to mature into a form that you are finally happy to share them. This is an example for such thing. I got interested in the area of Philosophy of Technology during my PhD studies, and continue to explore it since. During this journey, I found a lot of inspiration and links […]![]()

Some ideas take long time to mature into a form that you are finally happy to share them. This is an example for such thing. I got interested in the area of Philosophy of Technology during my PhD studies, and continue to explore it since. During this journey, I found a lot of inspiration and links […]![]()

If you going to this years AAG, you might be interested in our Geosimulation Models sessions which will take place on Wednesday the 9th of April from 10am.

Session Description: Since the publication of Geosimulation in 2004, the use of Agent-based Modeling (ABM) and Cellular Automata (CA) under the umbrella of Geosimulation models within geographical systems have started to mature as methodologies to explore a wide range of geographical and more broadly social sciences problems facing society. The aim of these sessions is to bring together researchers utilizing geosimulation techniques (and associated methodologies) to discuss topics relating to: theory, technical issues and applications domains of ABM and CA within geographical systems.

If you going to this years AAG, you might be interested in our Geosimulation Models sessions which will take place on Wednesday the 9th of April from 10am.

Session Description: Since the publication of Geosimulation in 2004, the use of Agent-based Modeling (ABM) and Cellular Automata (CA) under the umbrella of Geosimulation models within geographical systems have started to mature as methodologies to explore a wide range of geographical and more broadly social sciences problems facing society. The aim of these sessions is to bring together researchers utilizing geosimulation techniques (and associated methodologies) to discuss topics relating to: theory, technical issues and applications domains of ABM and CA within geographical systems.

We recently contributed a chapter to “Big Data: Techniques and Technologies in Geoinformatics” entitled “Geoinformatics and Social Media: A New Big Data Challenge” where we explore how social media and ambient geographic information is transforming geo…

Continue reading »

We recently contributed a chapter to “Big Data: Techniques and Technologies in Geoinformatics” entitled “Geoinformatics and Social Media: A New Big Data Challenge” where we explore how social media and ambient geographic information is transforming geo…

Continue reading »The news that Roger Tomlinson, famously ‘the father of GIS‘, passed away few days ago are sad – although I met him only few times, it was an honour to meet one of the pioneers of my field. A special delight during my PhD research was to discover, at the UCL library the proceedings of […]![]()

The Guardian’s Political Science blog post by Alice Bell about the Memorandum of Understanding between the UK Natural Environment Research Council and Shell, reminded me of a nagging issue that has concerned me for a while: to what degree GIS contributed to anthropocentric climate change? and more importantly, what should GIS professionals do? I’ll say from the start […]![]()

Once upon a time, Streetmap.co.uk was one of the most popular Web Mapping sites in the UK, competing successfully with the biggest rival at the time, Multimap. Moreover, it was ranked second in The Daily Telegraph list of leading mapping sites in October 2000 and described at ‘Must be one of the most useful services on […]![]()

Over the last month or so I’ve been involved in some consultancy work for the Evening Standard. The task was to develop a map to communicate the extension of the newspaper’s distribution network, a plan that was announced on their website and went into action last week. The work involved the production of three maps, …

Read more →

I’ve been exploring ways to map urban land-use diversity, which is a rather tough nut to…

Continue reading »I’ve been exploring ways to map urban land-use diversity, which is a rather tough nut to…

Continue reading »I’ve been exploring ways to map urban land-use diversity, which is a rather tough nut to…

Continue reading »I’ve been exploring ways to map urban land-use diversity, which is a rather tough nut to…

Continue reading »

In his book “A Framework for Geodesign: Changing Geography by Design” Karl Steinitz brings his vast experience as a landscape architect and planner to such an issue. For those not familiar to the term geodesign, Steinitz (2012) writes in his preference to the book that it “is an invented word, and a very useful term to describe an activity that is not the territory of any single design profession, geographic science or information technology” (p ix). More generally Steinitz (2012) frames geodesign as “the development and application of design-related processes intended to change the geographical study areas in which they are applied and realised” (p1). Or another way of putting it, the merging of geography and design through computers. This is reiterated later on by a quote from Michael Flaxman were he states “Geodesign is a design and planning method which tightly couples the creation of design proposals with impact simulations informed by geographic contexts, systems thinking, and digital technology” (Flaxman quoted in Steinitz, 2012 p 12).

Moreover, geodesign can be considered both as a verb and as a noun which Steinitz relates to design more generally (see Steinitz, 1995). In the sense as a verb, geodesign is about asking questions and as a noun, geodesign is the content of the answers. In this book Steinitz not only clears up the meaning of geodesign but more importantly provides a comprehensive framework (based on his past work) for thinking about strategies of geodesign, and for organising and operationalizing these meanings.

The book is made up of twelve chapters and split into four parts. The first part is spent on framing geodesign and to set the scene for the remainder of book. For example, chapter 1 notes that for geodesign to be successful, one requires collaboration between the design professions (e.g. architects, planners, urban designers, etc.), geographical sciences (e.g. geographers, ecologists, etc), information technologies and those people living within the communities where geodesign is being applied. This is reiterated throughout the book. Chapter 1 also traces the history of geodesign, and how the advent of computer methods for the acquisition, management and display of digital data can be used to link many participants, thus making design not a solitary activity. Chapter 2 introduces the reader to the context for geodesign in the sense that 1) geography matters and that different societies think differently about their geography, 2) scale maters in the sense of what scale should a geodesign project be applied at (e.g., local, regional or global), and what are the appropriate considerations that need to incorporated at each scale, and finally 3) size matters, if the size of the geographic study area increases, there is a high risk of a harmful impact if one makes a mistake.

Part 2 of the book lays out a framework for geodesign. It is important to note that Steinitz does not call this a methodology for geodesign, as he argues one cannot have a singular methodology as the approaches, principles and methods are applied to projects across a range of geographies, scales and sizes. He therefore introduces a framework as a verb, specifically for asking questions, choosing among many methods and seeking possible answers. In order to develop this framework Steinitz walks the reader through six different questions and types of models common in geodesign projects.

Chapter 3 focuses on components of the framework and the questions one needs to address for a successful geodesign project. These questions broadly range from: 1) How should the study area be described? 2) How does the study area operate? 3) Is the current study area working well? 4) How might the study area be altered? 5) What differences might the changes cause?, and finally, 6) How should the study area be changed? As posed by Steinitz, these questions are not a linear progression, but have several iterative loops and feedbacks both with the geodesign team and the application stakeholders. Moreover, Steinitz argues that such questions should be asked three times during the geodesign study, the first to treat them as why questions (e.g. to understand the geographic study area and the scope of the study). Secondly, the questions are asked in reverse order to identify the how questions (e.g. to define the methods of the study, therefore geodesign becomes a decision rather than data driven process) and finally, the questions are asked in sequential order to address the what, where and when questions as the geodesign study is being implemented. Once these three iterations are complete, there can be three possible decisions, yes, no and maybe. If maybe or no, more feedback is needed between the geodesign team and the stakeholders. These iterations highlight how geodesign is an on-going process of changing geography by design.

Overall the book is extremely well written and Steinitz provides a critical and personal account of geodesign, which shows his expertise in the area from his years of teaching and carrying out geodesign work. The use of figures and real world examples really helps support the discussion. But if you are looking for a textbook for “how to” do geodesign, or a list of technologies that enable geodesign, you need to look elsewhere. This is a book the principles and practice of geodesign in a general sense, and which provides a valuable resource for those interested in this topic.”

References:

Brail, R.K. (ed.) (2008), Planning Support Systems for Cities and Regions, Lincoln Institute of Land Policy, Cambridge, MA.

Ervin, S. (2011), ‘A System for GeoDesign’, Proceedings of Digital Landscape Architecture, Anhalt University of Applied Science, Dessau, Germany, pp. 145-154.

Goodchild, M.F. (2010), ‘Towards Geodesign: Repurposing Cartography and GIS?.’ Cartographic Perspectives, 66(7-22).

Longley, P.A., Goodchild, M.F., Maguire, D.J. and Rhind, D.W. (2010), Geographical Information Systems and Science (3rd Edition), John Wiley & Sons, New York, NY.

Steinitz, C. (1995), ‘Design is a Verb; Design is a Noun’, Landscape Journal, 14(2): 188-200.

Steinitz, C. (2012), A Framework for Geodesign: Changing Geography by Design, ESRI Press, Redlands. CA.

Full reference to the book:

Review of Steinitz, C. (2012), A Framework for Geodesign: Changing Geography by Design, ESRI Press, Redlands. CA.

Full reference to the review:

Continue reading »Crooks, A.T. (2013), Crooks on Steinitz: A Framework for Geodesign: Changing Geography by Design, Environment and Planning B, 40 (6): 1122-1124.

In his book “A Framework for Geodesign: Changing Geography by Design” Karl Steinitz brings his vast experience as a landscape architect and planner to such an issue. For those not familiar to the term geodesign, Steinitz (2012) writes in his preference to the book that it “is an invented word, and a very useful term to describe an activity that is not the territory of any single design profession, geographic science or information technology” (p ix). More generally Steinitz (2012) frames geodesign as “the development and application of design-related processes intended to change the geographical study areas in which they are applied and realised” (p1). Or another way of putting it, the merging of geography and design through computers. This is reiterated later on by a quote from Michael Flaxman were he states “Geodesign is a design and planning method which tightly couples the creation of design proposals with impact simulations informed by geographic contexts, systems thinking, and digital technology” (Flaxman quoted in Steinitz, 2012 p 12).

Moreover, geodesign can be considered both as a verb and as a noun which Steinitz relates to design more generally (see Steinitz, 1995). In the sense as a verb, geodesign is about asking questions and as a noun, geodesign is the content of the answers. In this book Steinitz not only clears up the meaning of geodesign but more importantly provides a comprehensive framework (based on his past work) for thinking about strategies of geodesign, and for organising and operationalizing these meanings.

The book is made up of twelve chapters and split into four parts. The first part is spent on framing geodesign and to set the scene for the remainder of book. For example, chapter 1 notes that for geodesign to be successful, one requires collaboration between the design professions (e.g. architects, planners, urban designers, etc.), geographical sciences (e.g. geographers, ecologists, etc), information technologies and those people living within the communities where geodesign is being applied. This is reiterated throughout the book. Chapter 1 also traces the history of geodesign, and how the advent of computer methods for the acquisition, management and display of digital data can be used to link many participants, thus making design not a solitary activity. Chapter 2 introduces the reader to the context for geodesign in the sense that 1) geography matters and that different societies think differently about their geography, 2) scale maters in the sense of what scale should a geodesign project be applied at (e.g., local, regional or global), and what are the appropriate considerations that need to incorporated at each scale, and finally 3) size matters, if the size of the geographic study area increases, there is a high risk of a harmful impact if one makes a mistake.

Part 2 of the book lays out a framework for geodesign. It is important to note that Steinitz does not call this a methodology for geodesign, as he argues one cannot have a singular methodology as the approaches, principles and methods are applied to projects across a range of geographies, scales and sizes. He therefore introduces a framework as a verb, specifically for asking questions, choosing among many methods and seeking possible answers. In order to develop this framework Steinitz walks the reader through six different questions and types of models common in geodesign projects.

Chapter 3 focuses on components of the framework and the questions one needs to address for a successful geodesign project. These questions broadly range from: 1) How should the study area be described? 2) How does the study area operate? 3) Is the current study area working well? 4) How might the study area be altered? 5) What differences might the changes cause?, and finally, 6) How should the study area be changed? As posed by Steinitz, these questions are not a linear progression, but have several iterative loops and feedbacks both with the geodesign team and the application stakeholders. Moreover, Steinitz argues that such questions should be asked three times during the geodesign study, the first to treat them as why questions (e.g. to understand the geographic study area and the scope of the study). Secondly, the questions are asked in reverse order to identify the how questions (e.g. to define the methods of the study, therefore geodesign becomes a decision rather than data driven process) and finally, the questions are asked in sequential order to address the what, where and when questions as the geodesign study is being implemented. Once these three iterations are complete, there can be three possible decisions, yes, no and maybe. If maybe or no, more feedback is needed between the geodesign team and the stakeholders. These iterations highlight how geodesign is an on-going process of changing geography by design.

Overall the book is extremely well written and Steinitz provides a critical and personal account of geodesign, which shows his expertise in the area from his years of teaching and carrying out geodesign work. The use of figures and real world examples really helps support the discussion. But if you are looking for a textbook for “how to” do geodesign, or a list of technologies that enable geodesign, you need to look elsewhere. This is a book the principles and practice of geodesign in a general sense, and which provides a valuable resource for those interested in this topic.”

References:

Brail, R.K. (ed.) (2008), Planning Support Systems for Cities and Regions, Lincoln Institute of Land Policy, Cambridge, MA.

Ervin, S. (2011), ‘A System for GeoDesign’, Proceedings of Digital Landscape Architecture, Anhalt University of Applied Science, Dessau, Germany, pp. 145-154.

Goodchild, M.F. (2010), ‘Towards Geodesign: Repurposing Cartography and GIS?.’ Cartographic Perspectives, 66(7-22).

Longley, P.A., Goodchild, M.F., Maguire, D.J. and Rhind, D.W. (2010), Geographical Information Systems and Science (3rd Edition), John Wiley & Sons, New York, NY.

Steinitz, C. (1995), ‘Design is a Verb; Design is a Noun’, Landscape Journal, 14(2): 188-200.

Steinitz, C. (2012), A Framework for Geodesign: Changing Geography by Design, ESRI Press, Redlands. CA.

Full reference to the book:

Review of Steinitz, C. (2012), A Framework for Geodesign: Changing Geography by Design, ESRI Press, Redlands. CA.

Full reference to the review:

Continue reading »Crooks, A.T. (2013), Crooks on Steinitz: A Framework for Geodesign: Changing Geography by Design, Environment and Planning B, 40 (6): 1122-1124.

There is something in the physical presence of book that is pleasurable. Receiving the copy of Introducing Human Geographies was special, as I have contributed a chapter about Geographic Information Systems to the ‘cartographies’ section. It might be a response to Ron Johnston critique of Human Geography textbooks or a decision by the editors to extend the […]![]()

|

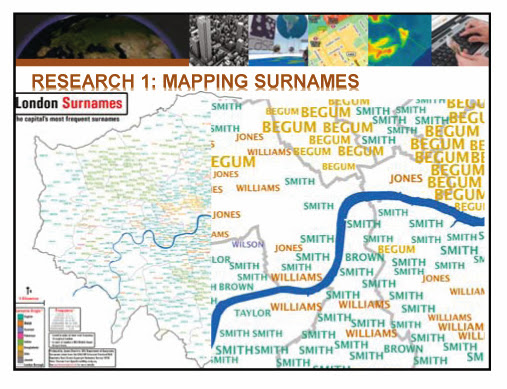

| Image 1 |

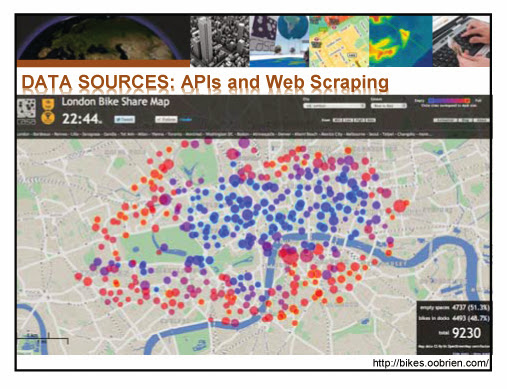

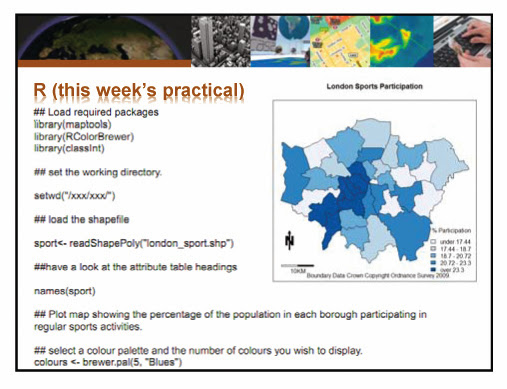

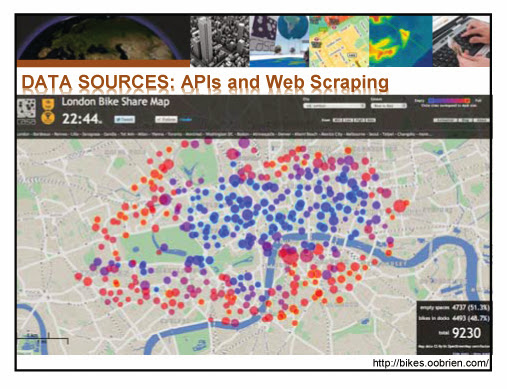

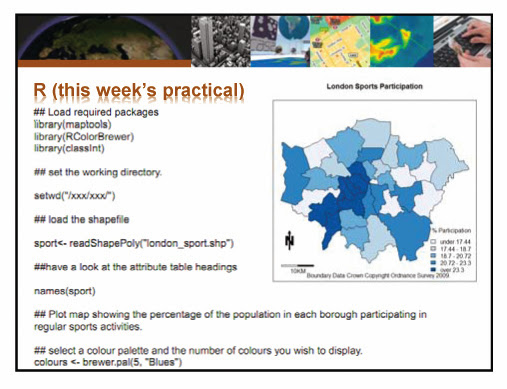

And then, he moved to GIS software industry which has been significantly growing. As interest and the utilisation of GIS are increasing, GIS software market is expanding almost 10% every year and now it is used in all industries and public sectors such as business, public safety, military and education. The popular GIS tools: Arc GIS, MAP Info, Quantum GIS, Pythonand R, and specific points of each tool were introduced. Also, small description of GIS cloud and online GIS tools was following. (Image 2)

|

| Image 3 |

|

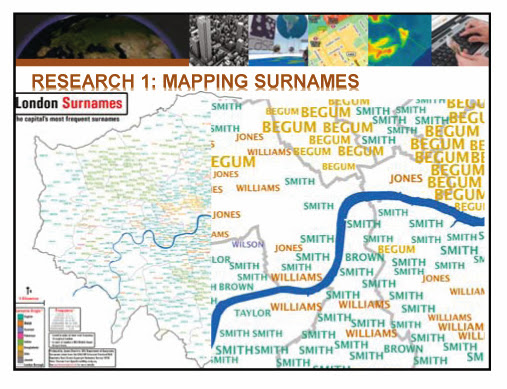

| Image 4 |

Continue reading »

|

| Image 1 |

And then, he moved to GIS software industry which has been significantly growing. As interest and the utilisation of GIS are increasing, GIS software market is expanding almost 10% every year and now it is used in all industries and public sectors such as business, public safety, military and education. The popular GIS tools: Arc GIS, MAP Info, Quantum GIS, Pythonand R, and specific points of each tool were introduced. Also, small description of GIS cloud and online GIS tools was following. (Image 2)

|

| Image 3 |

|

| Image 4 |

Continue reading »

The second lecture of GIS comprised mainly three parts, the examples of practical research by using GIS, GIS software and the way to gain relevant data for the research. In the beginning, Dr. Adam Dennett, the lecturer of CASA, informed the…

Continue reading »

|

| Image 1. Dr.Adam Dennett introduced the course outline on 2nd October, 2013 |

Continue reading »

|

| Image 1. Dr.Adam Dennett introduced the course outline on 2nd October, 2013 |

Continue reading »

Image 1. Dr.Adam Dennett introduced the course outline on 2nd October, 2013From this academic term, Networking City is doing a teaching assistant role for ‘GEOGRAPHIC INFORMATION SYSTEMS AND SCIENCE’ course which is set up by CASA for their prov…

Continue reading »

In a move to understand slums, we have switch gears slightly from agent-based modeling to a more statistical study of slums. To this end we have just received word that our paper entitled “Measuring Slum Severity in Mumbai and Kolkata: A Househol…

Continue reading »

In a move to understand slums, we have switch gears slightly from agent-based modeling to a more statistical study of slums. To this end we have just received word that our paper entitled “Measuring Slum Severity in Mumbai and Kolkata: A Househol…

Continue reading »

The international community can be viewed as a set of networks, manifested through various transnational activities. The availability of longitudinal datasets such as international arms trades and United Nations General Assembly (UNGA) allows for the study of state-driven interactions over time. In parallel to this top-down approach, the recent emergence of social media is fostering a bottom-up and citizen driven avenue for international relations (IR). The comparison of these two network types offers a new lens to study the alignment between states and their people. This paper presents a network-driven approach to analyze communities as they are established through different forms of bottom-up (e.g. Twitter) and top-down (e.g. UNGA voting records and international arms trade records) IR. By constructing and comparing different network communities we were able to evaluate the similarities between state-driven and citizen-driven networks. In order to validate our approach we identified communities in UNGA voting records during and after the Cold War. Our approach showed that the similarity between UNGA communities during and after the Cold War was 0.55 and 0.81 respectively (in a 0-1 scale). To explore the state- versus citizen-driven interactions we focused on the recent events within Syria within Twitter over a sample period of one month. The analysis of these data show a clear misalignment (0.25) between citizen-formed international networks and the ones established by the Syrian government (e.g. through its UNGA voting patterns).

Full reference:

Crooks, A.T., Masad, D., Croitoru, A., Cotnoir, A., Stefanidis, A. and Radzikowski, J. (2013), International Relations: State-Driven and Citizen-Driven Networks, Social Science Computer Review. DOI:10.1177/0894439313506851

|

| Arms transfers |

The international community can be viewed as a set of networks, manifested through various transnational activities. The availability of longitudinal datasets such as international arms trades and United Nations General Assembly (UNGA) allows for the study of state-driven interactions over time. In parallel to this top-down approach, the recent emergence of social media is fostering a bottom-up and citizen driven avenue for international relations (IR). The comparison of these two network types offers a new lens to study the alignment between states and their people. This paper presents a network-driven approach to analyze communities as they are established through different forms of bottom-up (e.g. Twitter) and top-down (e.g. UNGA voting records and international arms trade records) IR. By constructing and comparing different network communities we were able to evaluate the similarities between state-driven and citizen-driven networks. In order to validate our approach we identified communities in UNGA voting records during and after the Cold War. Our approach showed that the similarity between UNGA communities during and after the Cold War was 0.55 and 0.81 respectively (in a 0-1 scale). To explore the state- versus citizen-driven interactions we focused on the recent events within Syria within Twitter over a sample period of one month. The analysis of these data show a clear misalignment (0.25) between citizen-formed international networks and the ones established by the Syrian government (e.g. through its UNGA voting patterns).

Full reference:

Crooks, A.T., Masad, D., Croitoru, A., Cotnoir, A., Stefanidis, A. and Radzikowski, J. (2013), International Relations: State-Driven and Citizen-Driven Networks, Social Science Computer Review. DOI:10.1177/0894439313506851

|

| Arms transfers |

Two of our recent papers have been featured in IQT Quarterly. The first looks at completeness and error in VGI and the second features some of our work on social media and polycentric communities. The papers have been significantly shortened and …

Continue reading »

Two of our recent papers have been featured in IQT Quarterly. The first looks at completeness and error in VGI and the second features some of our work on social media and polycentric communities. The papers have been significantly shortened and …

Continue reading »